The moon! She had disappeared for weeks; was she now returning? Had she been faithless to the Earth? and had she now approached to be a satellite of the new-born world?

“Impossible!” said Lieutenant Procope; “the Earth is millions upon millions of leagues away, and it is not probable that the moon has ceased to revolve about her.”

“Why not?” remonstrated Servadac. “It would not be more strange than the other phenomena which we have lately witnessed. Why should not the moon have fallen within the limits of Gallia’s attraction, and become her satellite?”

“Upon that supposition,” put in the count, “I should think that it would be altogether unlikely that three months would elapse without our seeing her.”

“Quite incredible!” continued Procope. “And there is another thing which totally disproves the captain’s hypothesis; the magnitude of Gallia is far too insignificant for her power of attraction to carry off the moon.”

“But,” persisted Servadac, “why should not the same convulsion that tore us away from the Earth have torn away the moon as well? After wandering about as she would for a while in the solar regions, I do not see why she should not have attached herself to us.”

“No, captain, no,” replied lieutenant Procope, “for one reason that cannot be gainsaid.”

“And what is that reason?”

“Because, I tell you, the mass of Gallia is so inferior to that of the moon, that Gallia would become the moon’s satellite; the moon could not possibly become hers.”

“I grant you that,” said Servadac. “But even assuming such to be the case—perhaps we are the moon of a moon. Perhaps the terrestrial satellite has been launched, by some catastrophe, around the solar system, and we are merely following?”

“And can you see,” said the lieutenant, interrupting him, “the reasons why such a hypothesis must be untenable?.”

Servadac smiled good-humouredly.

“I confess you seem to have the best of the argument,” he said. “For if Gallia had become a satellite of the moon, it would not have taken three months to catch sight of her. I suppose you are right.”

While this discussion had been going on, the satellite, or whatever it might be, had been rising steadily above the horizon, and had reached a position favourable for observation. Telescopes were brought, and it was very soon ascertained, beyond a question, that the new luminary was not the well-known Phoebe of terrestrial nights; it had no feature in common with the moon. Although it was apparently much nearer to Gallia than the moon to the Earth, its superficies was hardly one-tenth as large, and so feebly did it reflect the light of the remote sun, that it scarcely emitted radiance enough to extinguish the dim lustre of stars of the eighth magnitude. Like the sun, it had risen in the west, and was now at its full. To mistake its identity with the moon was absolutely impossible; not even Servadac could discover a trace of the seas, chasms, craters, and mountains which have been so minutely delineated in lunar charts, and it could not be denied that any transient hope that had been excited as to their once again being about to enjoy the peaceful smiles of “the queen of night” must all be resigned.

Count Timascheff finally suggested, though somewhat doubtfully, the question of the probability that Gallia, in her course across the zone of the minor planets, had carried off one of them; but whether it was one of the 169 asteroids already included in the astronomical catalogues, or one previously unknown, he did not presume to determine. The idea to a certain extent was plausible, inasmuch as it has been ascertained that several of the telescopic planets are of such small dimensions that a good walker might make a circuit of them in four and twenty hours; consequently Gallia, being of superior volume, might be supposed capable of exercising a power of attraction upon any of these miniature microcosms.

The first night in Nina’s Hive passed without special incident; and next morning a regular scheme of life was definitely laid down. “My lord governor,” as Ben Zoof until he was peremptorily forbidden delighted to call Servadac, had a wholesome dread of idleness and its consequences, and insisted upon each member of the party undertaking some special duty to fulfil. There was plenty to do. The domestic animals required a great deal of attention; a supply of food had to be secured and preserved; fishing had to be carried on while the condition of the sea would allow it; and in several places the galleries had to be further excavated to render them more available for use. Occupation, then, need never be wanting, and the daily round of labor could go on in orderly routine.

A perfect concord ruled the little colony. The Russians and Spaniards amalgamated well, and both did their best to pick up various scraps of French, which was considered the official language of the place. Servadac himself undertook the tuition of Pablo and Nina, Ben Zoof being their companion in play-hours, when he entertained them with enchanting stories in the best Parisian French, about “a lovely city at the foot of a mountain,” where he always promised one day to take them.

One question pertaining to etiquette was raised.

Ben Zoof very frequently presented the captain as the Governor General of the little colony. But, not content with granting him this title, he also made reference to Servadac as “Monseigneur” at every opportunity. This began to annoy Hector Servadac, who instructed his orderly not to bestow upon him this honorific.

“Nevertheless, Monseigneur,” Ben Zoof invariably replied.

“Curse you, idiot!”

“Yes, Monseigneur!”

Finally Captain Servadac could stand it no longer, and said to Ben Zoof:

“Will you please stop calling me Monseigneur?”

“Whatever you say, Monseigneur,” replied Ben Zoof.

“But, you pain in the neck, you know full well you’re still calling me it!”

“No, Monseigneur.” “Do you know what this word you’re so fond of using actually means?” “No Monseigneur.”

“So! Let me tell you, it’s the Latin for ‘mon vieux’. Do you have such poor respect for your superior officer as to refer to him in such a manner?”

And, truth to tell, after this little lesson, the honorific completely disappeared from Ben Zoof’s vocabulary.

The end of March came, but the cold was not intense to such a degree as to confine any of the party to the interior of their resort; several excursions were made along the shore, and for a radius of three or four miles the adjacent district was carefully explored. Investigation, however, always ended in the same result; turn their course in whatever direction they would, they found that the country retained everywhere its desert character, rocky, barren, and without a trace of vegetation. Here and there a slight layer of snow, or a thin coating of ice arising from atmospheric condensation indicated the existence of superficial moisture, but it would require a period indefinitely long, exceeding human reckoning, before that moisture could collect into a stream and roll downwards over the stony strata to the sea. It seemed at present out of their power to determine whether the land upon which they were so happily settled was an island or a continent, and till the cold was abated they feared to undertake any lengthened expedition to ascertain the actual extent of the strange concrete of metallic crystallization.

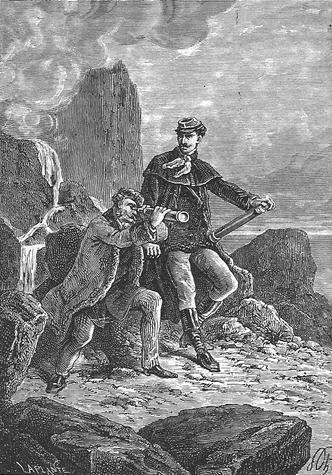

By ascending one day to the summit of the volcano, Captain Servadac and the count succeeded in getting a general idea of the aspect of the country. The mountain itself was an enormous block rising symmetrically to a height of nearly 3,000 feet above the level of the sea, in the form of a truncated cone, of which the topmost section was crowned by a wreath of smoke issuing continuously from the mouth of a narrow crater.

Under the old condition of terrestrial things, the ascent of this steep acclivity would have been attended with much fatigue, but with the effect of the altered condition of the law of gravity, the travellers performed perpetual prodigies in the way of agility, and in little over an hour reached the edge of the crater, without more sense of exertion than if they had traversed a couple of miles on level ground. Gallia had its drawbacks, but it had some compensating advantages.

Telescopes in hand, the explorers from the summit scanned the surrounding view. Their anticipations had already realized what they saw. Just as they expected, on the north, east, and west lay the Gallian Sea, smooth and motionless as a sheet of glass, the cold having, as it were, congealed the atmosphere so that there was not a breath of wind. Towards the south there seemed no limit to the land, and the volcano formed the apex of a triangle, of which the base was beyond the reach of vision. Viewed even from this height, whence distance would do much to soften the general asperity, the surface nevertheless seemed to be bristling with its myriads of hexagonal lamellae, and to present difficulties which, to an ordinary pedestrian, would be insurmountable.

“Oh for some wings, or else a balloon!” cried Servadac, as he gazed around him; and then, looking down to the rock upon which they were standing, he added, “We seem to have been transplanted to a soil stranger than any ever displayed in a glass case at a museum.”

“And do you observe, captain,” asked the count, “how the convexity of our little world curtails our view? See, how circumscribed is the horizon!”

Servadac replied that he had noticed the same circumstance from the top of the cliffs of Gourbi Island.

“Yes,” said the count; “it becomes more and more obvious that ours is a very tiny world, and that Gourbi Island is the sole productive spot upon its surface. We have had a short summer, and who knows whether we are not entering upon a winter that may last for years, perhaps for centuries?”

“But we must not mind, count,” said Servadac, smiling. “We have agreed, you know, that, come what may, we are to be philosophers.”

“Ay, true, my friend,” rejoined the count; “we must be philosophers and something more; we must be grateful to the good Protector who has hitherto befriended us. Without the discovery of this volcano, we would surely have perished.”

“I have the firm hope, count, that its fires will not extinguish before the end.”

“What end, captain?”

“Whatever end God wills. He knows, and we must trust His mercy.”

For a few moments they both stood in silence, and contemplated land and sea; then, having given a last glance over the dreary panorama, they prepared to wend their way down the mountain. Before, however, they commenced their descent, they resolved to make a closer examination of the crater. They were particularly struck by what seemed to them almost the mysterious calmness with which the eruption was effected. There was none of the wild disorder and deafening tumult that usually accompany the discharge of volcanic matter, but the heated lava, rising with a uniform gentleness, quietly overran the limits of the crater, like the flow of water from the bosom of a peaceful lake. Instead of a boiler exposed to the action of an angry fire, the crater rather resembled a brimming basin, of which the contents were noiselessly escaping. Nor were there any igneous stones or red-hot cinders mingled with the smoke that crowned the summit; a circumstance that quite accorded with the absence of the pumice-stones, obsidians, and other minerals of volcanic origin with which the base of a burning mountain is generally strewn.

Captain Servadac was of opinion that this peculiarity augured favourably for the continuance of the eruption. Extreme violence in physical, as well as in moral nature, is never of long duration. The most terrible storms, like the most violent fits of passion, are not lasting; but here the calm flow of the liquid fire appeared to be supplied from a source that was inexhaustible, in the same way as the waters of Niagara, gliding on steadily to their final plunge, would defy all effort to arrest their course.

Before the evening of this day closed in, a most important change was effected in the condition of the Gallian Sea by the intervention of human agency. Notwithstanding the increasing cold, the sea, unruffled as it was by a breath of wind, still retained its liquid state. It is an established fact that water, under this condition of absolute stillness, will remain uncongealed at a temperature several degrees below zero, whilst experiment, at the same time, shows that a very slight shock will often be sufficient to convert it into solid ice. It had occurred to Servadac that if some communication could be opened with Gourbi Island, there would be a fine scope for hunting expeditions. Having this ultimate object in view, he assembled his little colony upon a projecting rock at the extremity of the promontory, and called Nina and Pablo out to him in front.

“Nina, my pretty one,” said Captain Servadac. “Do you think you could throw something into the sea?”

“I think I could,” replied the child, “but I am sure that Pablo would throw it a great deal further than I can.”

“Never mind, you shall try first.”

Putting a fragment of ice into Nina’s hand, he addressed himself to Pablo:

“Look out, Pablo; you shall see what a nice little fairy Nina is! Throw, Nina, throw, as hard as you can.”

Nina balanced the piece of ice two or three times in her hand, and threw it forward with all her strength.

A sudden thrill seemed to vibrate across the motionless waters to the distant horizon, and the Gallian Sea had become a solid sheet of ice!